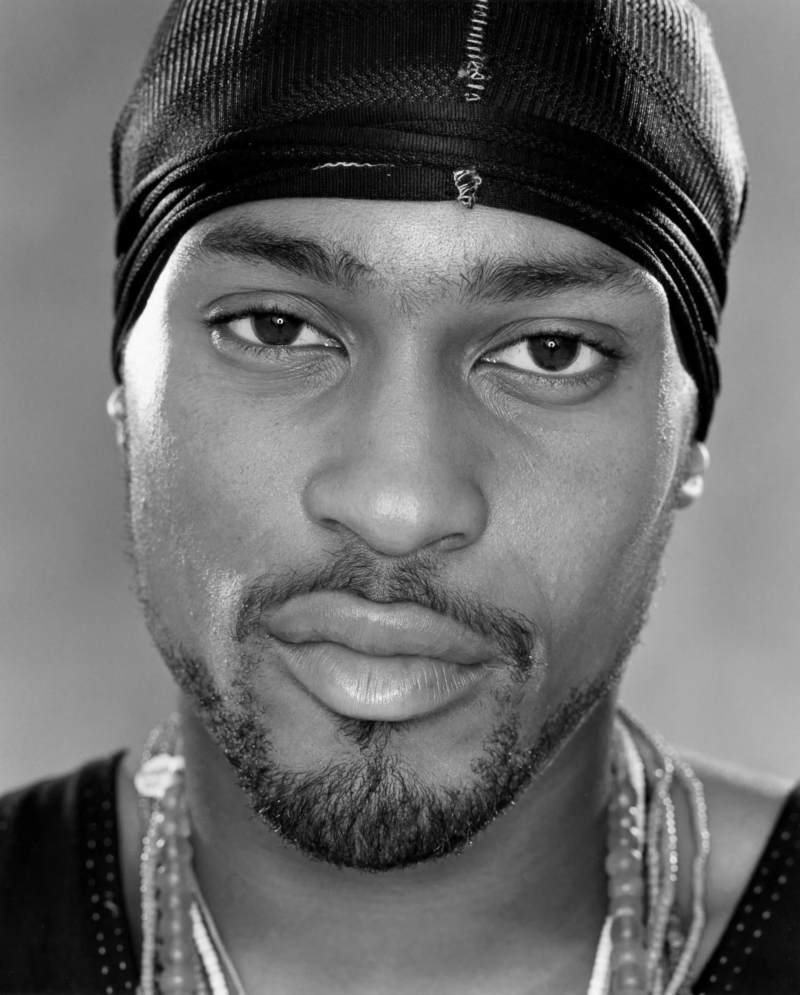

“I’m not trying to be like a poster child or anything of the movement, but definitely a voice—as a Black man, and as a concerned Black man and as a father.” (NPR Interview)

Michael D’Angelo Archer grew up in Richmond, Virginia, where his musical journey began at the age of three on the piano.

By five, he was in the church choir; by twelve, he was already training in classical music. Before adolescence, he’d mastered bass, guitar, and keyboards, defining himself as an early prodigy whose talents stretched across genres.

As a teen, D’Angelo took to the mic, winning talent shows and performing at the Apollo Theater at just 16 with a rendition of Johnny Gill’s “Rub You the Right Way.”

D’Angelo also started producing music early, forming the hip-hop group I.D.U. (Intelligent, Deadly, but Unique) with local collaborators Brian Trent and Ron Flowers.

“IDU’s shit was for real, man,” he recalled in his Red Bull Music Academy lecture, “We weren’t no joke.”

But just as formative as his technical training was, so was his religious upbringing. The son of a Pentecostal preacher, D’Angelo often pointed to the church as the foundation of his musical and spiritual identity.

“Growing up in the church, I saw that music was just as much a part of the ministry as the preacher opening up the Bible and preaching,” he told The Face in a 1999 interview. “When we’re onstage, we’re going straight to church. Pretty much every time, I start by praying.”

In between prayers, he was crate-digging, immersing himself in the blues, jazz, gospel, funk, and soul that would shape his sensibility.

“Blues was the nucleus of everything,” he told Nelson George in an interview, “A thread that was connecting it all.” D’Angelo’s debut album, Brown Sugar, was born in his bedroom in Richmond, its demos recorded on a four-track. Released in July 1995, the album didn’t just mark the arrival of a new talent, but helped define a new genre.

The term “neo-soul” would later be coined in part to describe the movement D’Angelo helped spark, along with artists like Erykah Badu, Maxwell, and Lauryn Hill.

At the time of its release, Brown Sugar was both a bold outlier that laid the foundation for D’Angelo’s more experimental future work, while still standing on its own as one of the most important and enduring R&B albums of the 1990s.

Not long after, D’Angelo became a core part of the Soulquarians, a collective of Black artists including Questlove, J Dilla, Erykah Badu, and Common.

Born at the legendary Electric Lady Studios in New York, the collective operated like a musical think tank whose ethos prided itself on collaboration.

“To me, Soulquarians was definitely just a collective of like-minded individuals,” D’Angelo told NPR. “It’s not gonna just be one group… it’s gonna be a movement. It’s gonna be all of us.”

Together, they created some of the most important albums of the era, like Water for Chocolate, Mama’s Gun, Things Fall Apart, with D’Angelo’s Voodoo as its crown jewel.

"The fight, our fight, is to bring the music back to what it’s supposed to be about, which is the craft and skills, not money and all this other bullshit. The question is: are we gonna take the path of artistry? Or are we going someplace else?” (The Face, 1999)

Where D’Angelo’s debut album, Brown Sugar, introduced his voice and soul sensibility, Voodoo is where he extended it, complicated it, and made something more ambitious.

Released on January 25, 2000, Voodoo marked a bold second chapter for D’Angelo. Critics hailed it as a masterpiece. One review described it as “designed and willed and technically optimised to be a testament for the ages … a rare accomplishment” in contemporary R&B.

“You also have to understand,” Questlove (friend and fellow Soulquarian member) told NPR, “that when Voodoo came out, it was a hard pill for a lot of people to swallow. It sounded like an acid trip. Now it’s in our DNA.”After the release of Voodoo, the glare of celebrity became unbearable. The sexualisation of the “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” video reduced his artistry to flesh, and behind the scenes, he spiraled, wrestling with addiction, grief, and the crushing pressure to deliver a follow-up.

In the years that followed, D’Angelo largely disappeared from public view, re-emerging only occasionally. His absence became part of his mythology. But his influence never waned. After fourteen years, he finally released his third album, Black Messiah.

Devil’s Pie: D’Angelo, the 2019 documentary, marked his return and offered a rare window into an artist famously private, shedding light on the cost of genius and the toll of a system that feeds on Black excellence while rarely protecting it.

Raw and political, Black Messiah was D’Angelo’s response to a world on fire: Ferguson, Eric Garner, Black Lives Matter, rising surveillance, and social fracture.

Tracks like “The Charade” and “1000 Deaths” were blistering and confrontational, while “Really Love” and “Prayer” returned to a deeper intimacy. It was both personal and collective, political and spiritual.

“I didn’t name this album Black Messiah to glorify one man,” D’Angelo wrote in the liner notes. “It’s about all of us. It’s about the voice of the people.” Released in a moment of racial reckoning, Black Messiah sounded like both resistance and revival.

To this day, D’Angelo’s fingerprint is everywhere. His influence bleeds across genres and continents—felt in the vulnerable minimalism of Frank Ocean, the textured layering of Solange, the rhythmic looseness of Anderson .Paak, and the experimental soul of artists like Sampha and Lianne La Havas.

In underground circles and academic spaces, D’Angelo’s music had always been more than sound, and his death has been felt all over the world. In a WAKUU TV obituary, he was described as someone who “was more than a voice; he was a feeling.”

In academic discussions of Black musical genius, he is now spoken of alongside Prince, Sly Stone, and Stevie Wonder.

Artists from every corner of the world have cited him as an influence. Community radio stations across Richmond, Detroit, New York, and London have scrambled to put together tribute shows. More than a sound, he left a structure: a blueprint for how to hold church in the studio, onstage, and in the hearts of those who listened.

“The last pure singer on earth” – Questlove, Devil’s Pie Documentary, 2019

Radio Resources:

-

Soup to Nuts w/ Shy One – NTS Radio (Oct 15, 2025)

-

ESK: Charlotte Dos Santos – A D’Angelo Tribute (Rinse FM, Oct 15, 2025)

-

Think Outside the Kiosk w/ Lefto Early Bird – D’Angelo Tribute (Kiosk Radio, Oct 19, 2025)

-

Budgie – NTS Radio (Oct 16, 2025)

-

To The Left Radio w/ Donnie Sunshine – Foundation FM

-

Ross Allen – NTS Radio (Oct 18, 2025)

-

Giles Peterson –BBC 6 (Oct 18, 2025)