Rap music is a tough sell. It’s violent and misogynistic. It's crass and confrontational in nature, and, despite what the blogs may tell you, it doesn’t particularly resonate with the masses, at least not on a commercial level. While hip-hop continues to dominate pop culture, it is sinking on the charts; according to the Neilson & Billboard’s 2012 Music Industry Report, rap has dropped a startling -11.40% over the last year, standing just ahead of genres like New Age and Jazz and Latin. A poll conducted by Public Policy Polling — one of the most accurate pollsters in the nation — revealed that 50% of people consider rap their least favorite genre, and 68% view it unfavorably. Only nine rap acts in history have ever tapped into a truly commercially viable mainstream rap market: Tupac Shakur, Notorious B.I.G., Jay-Z, Eminem, Nelly, 50 Cent, OutKast, Kanye West, and Lil Wayne. These are the outliers, and they managed to beat the odds with lasting (or in a few cases fleeting) crossover appeal and/or continually rich character development — something about each aforementioned artist defied rap convention. Each act possessed a rare magnetism that drew diverse crowds, and together they've collectively established a blueprint for how to amass nearly universal intrigue: be an interesting character or be a relatable one.

As Aubrey Drake Graham begins to divulge now slightly revised versions of his ascension with greater clarity while also rewriting his own rap mythology, he is slowly starting to resemble Leonardo DiCaprio as Billy Costigan. Costigan is a character in Martin Scorcese's epic, Academy Award-winning film "The Departed," and he is as complex a character as Graham when fleshed out; a Boston man born the son of a notorious gangster and an affluent matron seeking penance for his family's sins as an undercover cop. When Costigan's past is laid bare, it's clear he's had a very difficult journey of self-discovery, one that –as it turn out — will never truly be fulfilled. "You were kind of a double kid, I bet, right? Huh? One kid with your old man, one kid with your mother. You're upper-middle class during the weeks, then you're droppin' your "R"s and you're hangin' in the big, bad Southie projects with your daddy, the fuckin' donkey on the weekends. I got that right?" Drake is that kid: upper-middle class namedropping Cappadonna and interpolating "C.R.E.A.M." in his outro, tinkering with musical equations — with rap as the variable — out of curiosity. He is Costigan, attempting to associate himself with something he's not, dropping his "R"s and stepping out of his comfort zone. "I find peace knowing that it's harder in the streets / I know. Luckily, I didn't have to grow there / I just used to go there 'cause it's niggas that I know there," he raps in a song ironically entitled "Wu-Tang Forever," and together, these two quotes perfectly encapsulate the Toronto rapper's appeal: he represents embracing rap from a safe distance.

Maybe it's the commitment to melody — sometimes to a detriment — or the conversational, relational affect of his words and tones or his widely publicized background as a cast member on a teen drama marketed to the Backstreet Boys demographic, but Drake has never felt hip-hop. Few would think to classify him an emcee in the truest, KRS-One-esque sense of the word, and that's because the traditional elements of hip-hop culture — the same ones that made rap such a divisive agent in the '80s and '90s — aren't particularly present in his music. Take Care was a rather transparent example of this, and outside of the obviously anti-rap, over-romanticized complexity of post-Napster teenage relationships portrayed by the music (which aspired to capture the angst of millennials dealing with text message breakups and social media-corrupted friendships), it understatedly defied rap convention like never before: it sought to change it. Over a year later, an album that was as much R&B as Lauryn Hill's The Miseducation Of… won the Grammy for Best Rap Album.

So, how did that one kid from Degrassi become the clear-cut king of mainstream rap in less than five years? He restructured it. There are no traces of Kool G Rap in Drake's music. You can't put his LPs side-by-side on shelves next to Mobb Deep or Smif-N-Wesson, and there certainly isn't even the slightest kinship to the Wu-Tang Clan despite his repeated championing. No, this is a new, far more palatable form of rap music that distances itself from the true socio-political essence of the craft. “[I’m] on a mission trying to shift the culture,” Drake howls boisterously in what, for all intensive purposes, serves as his opening statements on his third studio effort, and, for all intensive purposes, he has already accomplished what he set out to: never has a generation connected with with a rap artist this deeply or this swiftly, and never has an artist so successfully dodged the trappings of rap's rugged, obtuse perception. There's a reason every song sounds like Drake featuring Drake. As his story continues to unfold, Drizzy Drake is proving to be both an interesting character and a relatable one, and as his clout grows, so does his confidence. With his latest offering, Drake solidifies himself as possibly rap's most commercially viable act ever, and revels in the knowledge of that fact while doing so.

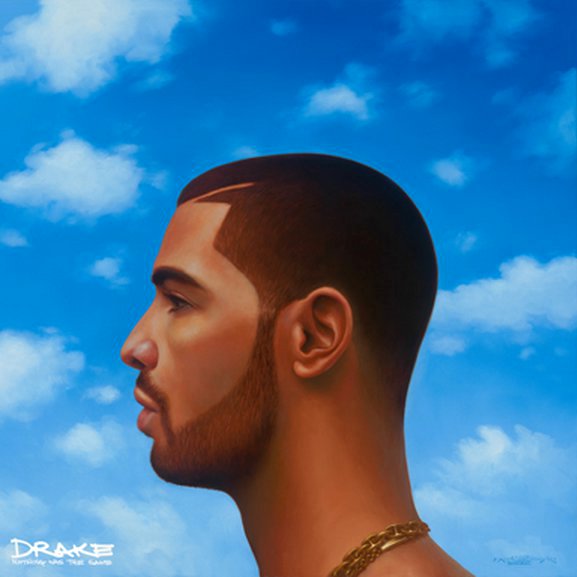

The album is entitled Nothing Was The Same, but, in actuality, a great deal remains unchanged. Everything feels dubiously familiar. The music can stray only but so far from its original motifs. Drake went on record saying this record was a conscious change of direction that sought to break his conventional formula, but this album is laid out almost precisely like his previous one just without the filler. And perhaps that is the greatest change if not the only change; NWTS transmits suburban plight cleaner and crisper than ever.

NWTS is without question the most succinct, concise delivery of Drake’s patented brand of emo-rap to date and it finds him balancing his precise musical equation — (rap + R&B) + emotional resonance = hit record — with stunning perfection. While it does tone down the emoting a few notches, there is still plenty of nostalgia-inducing reflection. This album has far more bite than any of his previous efforts, though, something that can be attributed to his growing consciousness regarding his own impact, and it comes as sort of a bittersweet gift. Drake has always been extremely self-aware, and as his stock continues to rise and he continues to climb the ranks of the rap caste system he grows more bold on wax. Fans have always sought more raps from the kid, and it seems like they're getting that now, but this new found bravado has Drake venturing into borderline fictitious territory. He's right on the precipice. Somehow, though, the balance is preserved not by a sense of realism but by the refreshing nature of a rapper frequently tagged as soft displaying machismo. He never raps with any real vitriol, but there is often incredible depth to his shots even if his threats are empty.

Drake did warn that his junior and senior would be meaner. This is a manifestation of that. It isn't the most intimidating of impressions — perhaps he should spend a bit more time with Migos, but it serves its purpose. As expected though, it's when he's not puffing out his chest that he produces his sharpest commentary and his best music. Songs like the Jhene Aiko-assisted "From Time" and the Sampha-assisted "Too Much" should strike a chord with anyone that experiences human emotions. They aren't tear jerking moments by any stretch, but they do prompt introspection. "Furthest Thing," which, one can speculate, led to the album title is a half-sung, half-rapped critique of the artist's activities pre and post-fame presented in a "then and now" sort of way, and it is a microcosm of what makes this effort such a success. Other highlights include the Jay Z-featured "Pound Cake/Paris Morton Music II"– the latter of which operates as a less aggressive expression of the sentiment made immortal by Kendrick Lamar in "Control," the boisterous "Worst Behavior," and the Hudson Mohawke-co-produced "Connect."

If Nothing Was The Same has any distinct shortcoming it's that the album isn't particularly adventurous. It doesn't explore any new themes or soundscapes (the production credits are littered with regulars and new producers signed to OVO Sound, conceivable to provide Drake with the same sounds that created the brand in the first place). It doesn't make any attempt to discuss anything of real consequence. Graham has been handed a platform with vast reach, and his decided repackaging of the exact message upon which his brand was built (on an album entitled Nothing Was The Same, no less) seems a bit of a disappointment.

In any case, Drake's Nothing Was The Same wins for being just as accessible as his last effort, but far less mushy. He has taken rap marketability to new levels by producing rap that doesn't make people uncomfortable, and in the same vein he has made himself relatable to an incredibly wide audience. Drake marks a changing of the guard of sorts, a reformatting of rap music as it is presented to the masses. Consumers have responded well to his approach and embraced the idea that rap can be consumed from outside the blast radius of everything that makes the genre so controversial and hard to like. They like him because they can relate to him more than any of his predecessors. His charisma is based less in braggadocio and more in a perceived sincerity. All the other stuff? He didn't live it; he witnessed it from his folks pad, and that makes it easier to swallow. "Just give it time, we'll see who's still around a decade from now. That's real," he raps with great conviction. Whether that is a mark of the music remains to be seen. One thing is evident, though: this guy isn't going anywhere anytime soon, and nothing will ever be the same as a result.