The concept of “Sonic Radiation & Metric Rotation” is central to your music. Can you explain what this means to you in both a compositional and experiential sense?

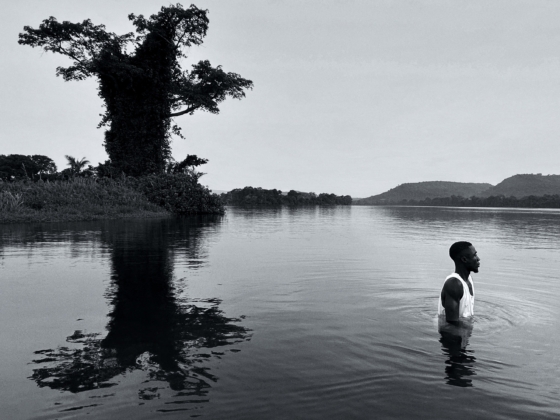

The term "Sonic Radiation & Metric Rotation" is meant to convey the idea that music is a spatial, even cosmic, phenomenon. Sound waves hit our bodies, move us, transform us, while we sit on a planet rotating at 1,600 km/h on its axis, orbiting the sun at 100,000 km/h, and spiraling around the center of our galaxy at another 800,000 km/h. We exist in an unimaginable vastness, yet we're rarely aware of it.

From a compositional perspective, this means I search for motion, rhythmic ovals, tonal clouds that organize themselves like a simplified, miniature reflection of the cosmos: structured, flowing, and inhabitable.

The multitrack player you developed for Cosmotonics 7×7 is revolutionary—allowing listeners to explore seven instrumentations of each piece in real time. What inspired this format, and how do you hope audiences will engage with it?

Yes, explore is the perfect word. I truly believe we’re meant to be explorers: to dive in, to immerse ourselves, to feel, to wait, and to observe what unfolds. Exploration takes time, patience, and dedication. Music, too, only reveals itself through time — it’s essentially time made audible.

There were many inspirations behind the multitrack player. Think of it this way: if I were an architect designing a building, I could view its outer form from various angles. But I could also step inside and discover a completely different world. I’d see the structure, the proportions, the light, the mood, the way it’s meant to be lived in.

As a listener of music, I am often offered—simply put—only the finished exterior from a single perspective, while countless details remain hidden within the body itself. Many times while listening, I’ve wished I could zoom in on those hidden details, which would mean leaving other elements aside in order to focus more precisely on one thing. That’s the kind of shift I wanted to offer: the ability to enter, to move closer, to experience intimacy.

There’s no hierarchy between the submixes. Each one, with all its intentional gaps, is conceived as a fully valid, standalone piece. Listeners can delve deeper, get to know each voice, develop a relationship through understanding — and then return to the often overwhelming density of the full mix with new clarity and calm.

You've collaborated with artists like Jojo Mayer, Skúli Sverrisson, and Peter Scherer. How do these partnerships influence the texture of your work, especially within such a modular and flexible framework like Cosmotonics?

Working with gifted artists is always a joy. First of all, they’re simply fascinating and curious people, and spending time with them, beyond rehearsals, recordings, and concerts, is deeply enriching.

My music, my structures, and beats require a certain level of skill, and when I work with Jojo, I get 150% back for every 100% I’ve written.

When composing, I usually know in advance who I’ll be playing with, and I tailor certain structures or methods to match their expected qualities.

Musicians with skill create spaces of possibility that sometimes only exert their effect as potentiality and ultimately can end in stillness.

So yes, the performers do shape the texture quite a lot, but less in terms of the core idea and more in the direct realization. I want each of my pieces, which I often describe as musical sculptures, to remain coherent and clear in every interpretation.

You’ve had a long-standing connection with your concert hall in Bern. How does space—both sonic and architectural—inform your composition process?

For more than 20 years, I’ve been running a concert hall in a large vaulted cellar in the old town of Bern. I wanted to change the way my music is consumed, or more beautifully put, how it is experienced. The standardized concert formats often no longer suited my music. I wanted the music to be played for 60 minutes without interruption, for moments of complete silence to be possible, for the aesthetic experience in the room to match the clarity of the music, and for the audience to be able to lie down and fully immerse themselves in the experience.

To support this, I abolished ticket sales. Instead, a group of people supports the space with a small monthly contribution, making free admission possible for everyone else. This had the lovely effect that a very diverse audience came to the concerts — and stayed, opened up, and enjoyed themselves.

I was able to develop my music there, rehearse it, and test it directly with an audience over the course of 20 years. That was highly instructive and encouraged me to become more consistent and radical. I stopped using set lists and played concerts lasting one hour, seven hours, or even 48 hours. I left out melodies, themes, B-sections, and solos to find out what actually carries the music.

I reflected on entertainment, challenge, and overwhelm, and I learned that the audience is open to everything, as long as I manage to help them truly engage with it. The place was always full. The only small drawback: it happens to be located in Bern, the relatively small capital of Switzerland…

Tell us more about the “Orbital Garden Satellite.” What led to the creation of this inflatable concert hall, and how does its design shape the listener’s physical and emotional experience of your music?

Yes, I developed the idea of a mobile Orbital Garden Satellite that could carry the atmosphere of the stationary Orbital Garden in Bern out into the world, independent of location. The Orbital Garden Satellite is a portable concert hall of around 110 square meters that can be set up within one or two hours.

In contrast to the vaulted cellar, the Satellite is mobile, lightweight, independent, and even externally symbolizes a visit from another world. It invites people not only to open themselves musically or temporally, but also spatially, as it represents another kind of place.

Standing in public space, it establishes a habitat, a greenhouse, so to speak, within the familiar, fast-moving outside world, separated only by a thin, semi-transparent skin.

For centuries, spaces have determined how music sounds, how it is performed, and how it is received. I believe that a different kind of music with different listening rituals also calls for different kinds of spaces.

It’s only partly about acoustics, since my music is transmitted into the space through an optimized sound system. More importantly, the space itself should embody an invitation and encourage a willingness to engage.

Its design, size, and furnishing are meant to guide the listener toward the music, to convey trust, and to open them up. It should take the visitor away from their daily routine, habits, and allow them to find time.

Much of your work explores reductionism. How do you find the balance between minimalism and emotional depth without sacrificing either?

In essence, I’m not particularly interested in reduction. As a concept, it can be fascinating and helpful in composition, it can enhance efficiency, accelerate processes, and create impact. But I rarely think about reduction, because I believe it is merely a byproduct of emancipation from being driven by something. If we closely examine this dynamic, reduction as an idea, as a concept, disappears.

I once went with my wife to a jazz concert. The virtuosity of the performance was high, the venue was full, and the routines were as one would expect. While my wife listened to the entire concert with great seriousness and focus, toward the end she turned to me and said, “These musicians have no impulse control.” She nailed it! I will be eternally grateful to her for this precise, simple formulation.

What is impulse control? Why do we often do more than is necessary? I think it’s because we are troubled by the feeling of not being enough. The fear of not measuring up, the fear of being nothing, or more fundamentally, the fear of non-being, leads us to pointless activism. When I am freed from this, when I am at peace with myself, space emerges. In this space, deep listening begins, and I realize that what is already sounding contains richness within itself, and my input is hardly needed anymore.

When I, as an artist, am able to confront this boundarylessness, concepts like reduction disappear, because they no longer play a role. From this center, what is created can even thrive in density and fullness, yet still seem coherent and logical. Nature knows no minimalism or maximalism; it is stylistically confident, and the more closely I observe it, the more it unfolds in every direction, both maximally and minimally.

So, when I am at peace with myself, I no longer need concepts, because I can trust my ears, my senses, my consciousness — or more precisely, the great consciousness. When I am focused, centered, in my core, and therefore free from fear, these terms fall away. I simply do it. I simply love it. This realization has something radical, which brings the circle back to reduction — but without concept.

You’ve composed for prestigious stages like the Lucerne Festival and received major accolades. How do you reconcile the institutional recognition of your work with its deeply personal and meditative nature?

Yes, that has happened too. But to be honest, it hasn't been a constant on my path. My need to challenge and question normality and conformity is only partially welcomed by renowned, institutional settings.

I see it as a fundamental prerequisite for an artist not to cooperate, and not to act opportunistically, but to dedicate themselves entirely and exclusively to what they love. If that love can be preserved, ideally without compromise, while performing on prestigious stages or receiving awards, then of course, that is a wonderful thing.

The scale of Cosmotonics 7×7—49 hours of music—is nearly overwhelming. How should a first-time listener approach the project? Is there an ideal entry point or mindset?

I believe the attitude is similar to the one we have towards our lives. Am I a researcher, someone who seeks the unknown? The unknown is always accompanied by a tolerable, enjoyable sense of overwhelm. I often seek music that joyfully overwhelms. Unfortunately, the events of the world constantly overwhelm us in such an unsettling way that, as a form of self-protection, we tend to shut ourselves off, risking, in turn, a state of ongoing intellectual and emotional under-stimulation.

But actually, I’d rather have a few more synapses in my brain at the end of the day than a few less. Well-measured overwhelm creates new synapses and leads to new ideas. Many years ago, when I first visited an exhibition by Matthew Barney, I was angry and upset by the overwhelming experience, but when I got home, I realized that it was an incredible, lifelong enrichment for me, and I loved him for that.

Yes, 49 hours of music can be overwhelming, and some may shy away from it. I recommend that a first-time listener first ask themselves if they want to invest in music they’ve never heard before. After that, I would suggest starting with one of the mainmixes and spending a few days immersed in that work, gradually exploring the submixes. I do believe that extended listening, in a comfortable chair, possibly in front of a good sound system, is worthwhile. The works have a dramaturgy, they make connections, and they build up. It’s similar to meditation: I have to sit down, and without expecting a specific result or immediate benefit, I allow myself to engage. Everything else happens on its own.

With only you and Brian Eno currently having access to the online platform, the project feels almost mythic. What’s next for Cosmotonics—do you envision opening it up more broadly, or is its exclusivity part of its philosophy?

Yes, that does sound mythical. And yes, Brian Eno does have access to Cosmotonics 7×7. Since Jojo Mayer works with Eno, he asked me if I could generate an access for him. I don’t know if Brian Eno has actually listened to Cosmotonics 7×7, but it’s nice to know that he can whenever he wants.

Of course, a few other people also have access to Cosmotonics 7×7, such as all the contributors or some artists whose work I truly admire. In addition, a few die-hard fans purchased access during the first test launch. Of course, I don’t want Cosmotonics 7×7 to remain an insider’s secret, and even if thousands of people were to explore this multi-player, it would still be highly exclusive compared to the major platforms. And yes, that’s part of the philosophy. I find large streaming platforms problematic. They favor those who already have an advantage and disadvantage those who are already at a disadvantage. With Cosmotonics 7×7, I have no chance of changing the overall course of the music industry in any way, but it embodies my attitude, which is that I’m willing to be less seen in order to follow what I truly believe in.

Change always begins on a small scale, and it’s often the small things that turn out to be the more interesting ones. That includes the fact that it’s often the more uncertain terrains because they haven’t been validated and “tested” by the majority. So, everyone has to trust their own perception and figure out whether they recognize quality in this small, new idea. It’s a much more exhausting process than just following what’s trending. That doesn’t mean that many of these trendy things don’t also contain quality, but it’s worth reflecting on the relationship.