Esteemed poet Emily Dickenson once stated that fame is a fickle food upon a shifting plate. The spotlight is a double edged sword, and those who are placed within are both rewarded by it's benefits and thwarted by it's scrutiny. Every year a handful of artists manage to tread faster than others, emerging from the underground and bursting forth into the light of recognition. It is these chosen few that we as audiophiles obsess over, marveling at their rise to fame and salivating over the good fortune. Yet as we scramble to jump aboard the bandwagon, we often overlook the treasures that show plain in hindsight. What is vogue right now might not be what's optimum, and it takes a disciplined ear to discount the decoys and find that honest, unruffled talent.

Doe Paoro epitomizes that talent. Despite a deep well of experience in a multitude of genres, there is a uniform feel of profound delicacy that lies in the heart of her work. Nothing feels conventional; the music is an eclectic conglomerate of styles ranging anywhere from Folk to Soul, however despite this eccentricity her music has a natural, familiar quality to it. Many bands strive for but are rarely able to achieve such relatable innovation within their work; often pushing so hard for progression that they lose sight of themselves, and thusly their audience. Doe Paoro is music true to its creator. She has no illusions about it, where it came from, or what its purpose is. She acknowledges her past and present influences with open arms, showing no shame in recognizing their presence in her products.

This earthly repose embodies not only her music, but an approach on life as a whole—an introspective understanding regarding the true nature of reality that the music is a product of. Rooted in the fabrics of love and guided by the liberating compass of meditation, her debut album Slow To Love valuably examines the crises in life that we all face and delivers answers from first hand experience. The songs within are raw in yearned for ways that our ever-changing industry fails to capture, true to its purpose and applicable to us all. Somehow Slow to Love went largely unnoticed, slipping through 2012 widely missed, and considering its universal relevance—it's a shame so many overlooked it.

Dreambear: "Born Whole (Live)"

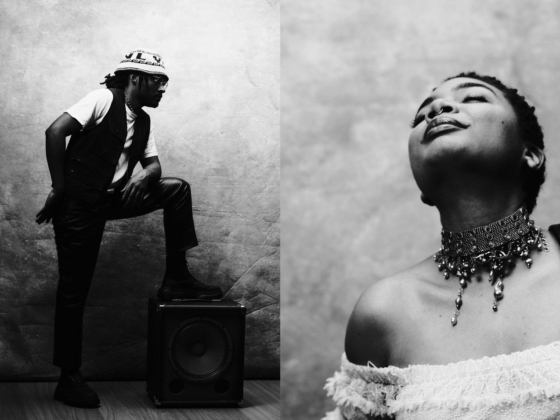

In our interview, Doe not only confirms that a new album is on the horizon, but that she may finally be receiving the recognition she deserves. Last week she returned to home in New York after working with Lasse Martin (Lykke LI, Niki & The Dove) in Stockholm on the upcoming album. Additionally, Justin Vernon (from Bon Iver) is producing one of her new singles, and she is a featured artist at SXSW next week.

[vimeo]https://vimeo.com/60686509[/vimeo]

. Dreambear . Facebook . Twitter . Soundcloud .

Recently she collaborated with Dreambear for a live session in which her band is described as "Enchanting, confident and tender." The session is the most recent in a string of intimate performances the production company has put together in an effort to showcase the little guys, offering professionally made products on a manageable platform. The riverside rendition of "Born Whole" (seen in the premiere above) showcases a deliberate variation from the original track. Slightly more complex, casual and aggressive, the performance is an uncorked glimpse into Doe's abilities as a singer, and the fluidity of her band as a whole.

Earmilk Interview: Doe Paoro

At first glance, Doe Paoro doesn't come off as any wiser than your average girl in their 20's: She's writhing around in mud and glitter in one of her videos—dancing on the shore in costumes in another. Her actions feel too free—too … untamed. That is, at first glance of course. Anything more and you will discover a reason for the wooded outfits and spiritual tone. There's a story behind it all, one that is no less intricate than it is nomadic, a story that pushed a girl away from a calling for so long that the barrier collapsed upon itself and she arrived anyway. Doe Paoro is somewhat the result of a spiritual awakening, a concept that felt unrealistic but became unavoidable.

She was on her last night in Stockholm when we did this interview, and even after a grueling day of last minute touches and travel preparations she managed to spend 12am to roughly 2am (her time) answering, conversing, and explaining herself to me while I sat on my bed at eating a bowl of spaghetti and drinking coffee. Not the fairest of situations, but 'tis the way these things work sometimes.

Stream: Doe Paoro – Slow To Love

[soundcloud url="https://api.soundcloud.com/playlists/1466331" params="" width=" 100%" height="450" iframe="true" /]

THE EARLY YEARS

EARMILK: One could, should they so choose, spend a few hours researching Doe Paoro. Yet, that's about where it would end—there simply is not enough info on yourself out there to make researching you an extensive task. Let's kick things off by looking into your history. When did you decide that you wanted music to be your career?

Doe Paoro: I've always been a musician. A career wasn't really something I ever considered, it was just something that … I kept doing? Just, every time I tried to stop doing it, to get a "real" career, or to walk down some other path, so to speak—something would happen, something else would interfere, and I would find myself back in music again. I would say the career came along when I stopped fighting that natural magnetism.

EM: Interesting. So from the get go the—how young were you when you first started playing music, or became interested in it?

DP: I put out my first album when I was 16, and it was just me and guitar. I made about 100 copies, and sold them in the town where I was from. That, essentially, was my first actual release, back in 2001.

EM: Essentially, what I'm trying to get at are the fetal stages of your musical inheritance, so to speak. So, were there people, or—when you were a kid, what pushed you onto music?

DP: I don't really come from a musical family. When I was younger, my grandfather was sort of an audiophile, and he would go out and see shows. He saw Billy Holliday probably a hundred times, and was really into making mix tapes for me, to share the music he loved. He grew up in the Bronx, and naturally when I was a child I was exposed to all these Jazz and Blues greats, Django Reinhardt tapes and Arethra Franklin cuts and some more really obscure stuff too.

EM: From early on this developed into a sort of exposed interest, where you essentially said to yourself "I enjoy this music thing, so I'm gonna continue to enjoy it and invest into it."?

DP: Yeah, and when I was a kid I always used to music when I went to sleep, and something about that really carried into adulthood, where music was consistently something that was soothing, and kept my dreams right.

EM: So you were one of those Walkmen kids who was always carrying a CD case, a walkman and a pair of headphones?

DP: (Laughs) I still do that. I guess it's more of your average iPod person approach these days, but I'm usually with or near by music in some way or another.

EM: (Laughing) Yeah I think most people are guilty of that these days, it's not as odd anymore. Last time we spoke you mentioned you were into Soul and Hip Hop, and as you just pointed at you've been that way for a while. So Item a) Do you Rap, and let's talk about those skills. Item b) Talk for a bit about some groups from back in the day who heavily influenced the music you make now, and not just groups you liked a lot when you were younger.

DP: Umm … (laughing) I may or may not have been in a rap collective that I generally keep under tab, so yes, I have … Rapped. In terms of seminal artists, The Fugees had one of the first albums I ever bought—Nina Simone was huge, Bob Marley and some Indian stuff like Ravi Shankar—

EM: Oh man, so you branch out. When I listen to your music, it's definitely different than a lot of things, but it feels in touch with a lot of current artists; For example, if I were to throw on "Born Whole", and then pick a track from a different artist to play next, I'd probably go to say … the new song "Retrograde" from James Blake.

DP: Well that's very clever of you because I love that song.

EM: Right, and as with him I don't think people generally listen to you music and say, like "Oh this person clearly used to listen to Hip Hop," but it is apparent that the Soul and Hip Hop—even the Blues—all seem to have influences here and there in the music you make now. You have an amazing voice that drives all of this, are you fluent with any instruments?

DP: I would say that I am definitely not fluent with any instruments (laughs). I play piano enough to write on it, and I play guitar enough to write on it, and I do compose on both of those and write or co-write on all of my songs—most of the songs on the album [Slow To Love] are co-written between me and Adam Rhodes, who plays in my band and helps produce. Also, in response to the other influences and other bands fitting in, you know—some of those albums I've listened to so many times that I don't even have to be referential, they become like a part of your DNA after a while.

EM: That's the way I feel about Blood Sugar Sex Magik by the Red Hot Chili Peppers (Laughs). You get to a point with albums that are so integral to your musical cognizance that you get to a point where someone could play a two second clip from any part of that album and you can identify what track it was—

DP: Yeah, exactly, and as a musician so many people compare me to other artists and I never intended to be like them but it makes sense, because their music affected me on such a deep level.

EM: Right, that is the right way to look at those sort of things, because a lot of artists don't really get offended, but they seem to always get defensive when you say they sound like someone. You get this whole "WELL yeah I'm not that person, OK?" reaction and from my end, it's like (laughing) "Yeah dude, I know you're not that person, I'm not an idiot, but you … sound like them."

DP: I feel like that defensiveness only reveals that they have a total complex issue about the fact that they totally did try and rip somebody off.

EM: Exactly, and the thing is, even if someone is ripping someone off—not that you do this—but Coldplay even has been frank about stealing ideas from smaller artists, and I think that's fine. If you're gonna rip someone off, whatever, as long as you do it well and you can acknowledge it, because in my opinion that's perfectly OK.

Moving back to being a musician as a young adult; You went to high school at a fairly large school in New York, and then out of nowhere you went to a small college in ohio to study [painting]. So you went to college for art and ended up working with music, which is really not that uncommon of a path—it's actually the same avenue I went down—But going from a big school like that to a smaller college in Oberlin, respectively, did that sort of school and that time in college play a big role in the way music shaped out for you?

DP: Again, not really—I don't know if I was just repressing it. It wasn't a coincidence I went to a school with a great music conservatory, you know? But that had nothing to do with it, and when I was at Oberlin most of the time I wasn't even doing anything with music. I'm self taught, musically, and I think I was really up tight—insecure even—about being in this academic music situations where people had all this formal training.

EM: So it was really just more of an uncomfortable feeling, where you'd be sitting in class and you'd know as well as anyone else how to make a good song but when someone started dropping their music theory on you, it was just like … (groans).

DP: Exactly! Music theory is just, like it was fine in 6th grade but I don't believe theory has nothing to do with knowing how to do or make music.

Creating music is an intuitive thing. Everything about it is intuitive, and more than anything else that's all you need.

EM: Right, I mean music theory does a great job of breaking down music and explaining how the pieces fit together and how everything works, but from a compositional and creative aspect you don't really need to know it. It can help you out, but—

DP: I'm sure it can, but creating music is an intuitive thing. Everything about it is intuitive, and more than anything else that's all you need.

EM: You're self taught, you learn by ear—when I think about that, being someone who gre up invested in music but is also multi-talented, you go to college and realize that's not the career you want, just happen in the music career without getting heavily in the "Societal" projection on how musical careers are supposed to play out (Sitting in music theory classes, for example), but you have that musical ear, so you sit in Theory classes and just kind of shrug your shoulders because you can just listen to a song and figure it out. The thing is, sixty percent or so of the class can't do that, so it's different for people like you and I who are able to listen to stuff and pick it up, well … People who have that innate knack for knowing how to do these things, they do them because they can. Not because they've learned to or trained to, which is something that seems apparent with you.

DP: I think it must be that way with any art. Education can help, but I also think education can hurt when it comes to creative things. whenever you lean on theory in a creative world—if you give up even an ounce of your intuition, I think it begins to harm more than help.

EM: Well right, I mean it puts a formula over something that should be completely open ended. It seems like after school, things started getting crazy. You were all over the place. In the scope of things, Doe Paoro seems to be a fairly new project for you. You've mentioned to me before that you've been in bands your whole life. Let's talk about those projects; Moving back to you album when you were sixteen, it was just you and your guitar and a recording device. What was that about?

DP: Well, it was such a sweet project for me. I don't even know what it's like, I mean the lyrics don't make a whole lot of sense—every once and a while you'll catch a line that's really poignant and sensitive and teenage in that sort of Holden Caulfield way. It sounds a little like Jewel, or Fiona Apple.

EM: Was it a project that came about just because you had a random urge to make something musically, or was there something more to it?

DP: I had this guitar lying around my parents house and I just began writing songs. I don't know how I got the idea to make an album—I wasn't in a band or anything, I didn't have anything planned in my head, I just kind of went for it and did it. I printed about a 100 copies once it was all said and done and then gave them out to friends and people around town.

SAN FRANCISCO & HIP HOP

EM: A few years down the road (about half a decade later) all of the sudden you're in San Francisco (laughs). You moved there, you got into a Blues Duo, that whole transitional period—

DP: Yeah, so what happened was—San Francisco was really where I started learning how to use my voice. It was where all my friends were, I had always heard the myths of California—There was this really amazing singer/trumpet player from Oberlin who was living in Cali. He had heard me sing once and my friend had told me to call him once I got in because he wanted me to sing in his band. I never ended up really singing in his band—He's now the lead man of The California Honeydrops—but I called him when I got there and he started giving me these voice lessons, just mentoring me in music which was something I'd never really thought about before.

He was playing me these old Irma Thomas records and we would talk about phrasing, or go line by line and figure out what she was doing. That's when I started really singing, and when I formed this blues thing with my friend Alia.

EM: So this blues duo was with your friend and not that guy?

DP: No, he was really a gateway into getting into it I guess.

EM: Ok, so this duo [Heaven With Your Boots On]—was that around the time when you seriously started to consider a musical future and taking it to the next level or were you still kind of flirting along the path of a side hobby, per se.

DP: You know, I guess it really opened me up to the idea of how much I really enjoyed it, but it still was you know, not something at the time I wanted to do as a career. At around that time I realized that I wanted to move back east and applied to be a New York City Teaching Fellow. I was accepted, then in that fall the fellowship got deferred, because the economy dropped at that time. So I basically had to figure out what I was going to do, and no surprise, I ended up falling back into music again.

EM: This would be the … Rap group?

DP: Well, yeah. (laughing) I mean the rap stuff is so ridiculous. I mean yes, but it didn't start out that way. It started out as this eight piece Soul band, and it was just going to be Soul. It was really fun and ridiculous, but then I started to date this guy who was a rapper, and we started making some music together. To this day everyone sort of feels like he was the Yoko Ono of the band, because he turned it into this ridiculous joke-rap project. I'm really glad it never got much publicity (laughs).

EM: Oh man. One day you're going to be really famous and at an awards show or something, and someone is going to have one of these tapes, and they're just going to plug it in on the loudspeakers and ruin your shining moment in the most hilariously rude way possible, and the video will go viral on Reddit (laughing), and you will inevitably be sucked into a revival rap project with a then washed up Lil' Wayne.

DP: I mean they're out their. It's a nightmare.

TRAVELING SOLO & TIBETAN OPERA

EM: So it seems like you had a casually good thing going, and then it turned into something else, and it fell apart. That's when you hit a wall with everything, and had this sort of "Hello World" moment, and disappeared for a while and traveled the world?

DP: Yeah that's pretty much it. Once I started that band I became really serious about it. That's when the idea of a career took shape, because a year later when the Teaching Fellowship came up again and it was time to join it, I was so heavily invested in the band that I was like "I'm just gonna pursue this for now" and gave that up. Then this happened and it hit a wall and couldn't move forward. It became really derivative, and was not really honest in the sense that it was this fun thing, but for me now that I had clarity—my creative states don't come when I'm having fun, they come when I'm having a meltdown—I'm not a performer. People who make fun joking music have to be good performers and that's it.

So that was breaking down, and I was ready to abandon music again when I hit that so called wall you spoke of. I had invested so much in the project and it was dying and I wasn't ready to accept that. My relationship at the time was also dying. I had always wanted to travel, and that seemed like a good time to do it. My plan was to become a Yoga instructor in India (which, obviously, didn't work out).

What makes you half of a person is your inability to learn from any situation, where you continue to go through life with blindfolds on. You get caught in this hellish cyclical existence.

EM: Well, it's interesting. You disappeared on your own (for the most part) and hit up Egypt, Greece, Israel—whatever—and then mostly India. That's wild, just to up and do out of the blue. But you were traveling solo, in foreign countries, as an attractive American female, out there finding yourself. Did you have any scary moments, being on your own like that?

DP: I know now it's a really sensitive time to be talking about being a female in a country like India with everything that's going on, but in my experience I didn't encounter any of that. Egypt on the other hand—that was a scary time. The time period when I was there was right around the Tahrir Square stuff, which was just the way the cards fell. I had planned my trip and was going from Israel into Egypt, and the revolution had just started. I had no idea what was going on. I had heard people were protesting in Cairo, and I thought maybe it would be like a one day thing, like when people protest in D.C. all the time. I just had no idea of the scale of things (laughs).

EM: Wow, so you really just wandered into one of the more iconically terrible times there of the past few decades or so. It must have been wild to experience. I think Americans have a skewed perception, like you can have a massive protest here, and eventually the cops will shut it down or something but you know you governments not going to just start killing you. You've experienced first hand that it's completely different in other parts of the world.

So you went from there and then Mumbai, so stepping into the India section of the trip. You still are very into meditation and yoga and bodily cleansing practices, particularly Vipassana Meditiation. Your experience there, what role did it play in your embracement and understanding of that lifestyle?

DP: Those things were enhanced, and I learned a lot about them in India. I've been practicing Yoga for about seven years now, but Vipassana I began practicing when my band started breaking down in New York. I actually did my first ten day silent retreat in Massachusetts.

EM: Did you do any direct studying while you were [in India]—did you get to go to Tibet or anything like that?

DP: I didn't get to got to Tibet, but I went to the main center of Vipassana in Maharashtra, which is like the state that Mumbai is in. I did a ten day meditation sit there, and that was really interesting because at that center they have a special area for people, some of whom are in meditation for forty five, even ninety days straight without speaking. It's on a totally different level, and it's pretty fascinating.

I studied with a bunch of different Yoga teachers while I was there—I was actually looking for one to teach me the whole time—but I was spending three or four days here and there for about five months. I ended up in Dombashawa, which is where the Dalai Lama lives. While I was there I got a bit lost and heard this music that was unlike anything I'd ever heard before. It turned out to be this school of Tibetan boys in this conservatory, basically. I was listening to this singing, and—this is the point in the story where music came back to me again.

I heard the singing and went to find the teacher who was leading the program and asked him to teach me. He said that he couldn't teach me if I wasn't a singer, so I told him to listen to me sing. Essentially, they couldn't teach this technique to someone who doesn't already have some music knowledge. I sang for him and he said that if he was going to teach me, I'd have to stay for at least a month would have to come every day.

My creative states don't come when I'm having fun, they come when I'm having a meltdown—I'm not a performer.

[soundcloud url="https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/80992344" params="" width=" 100%" height="166" iframe="true" /]

EM: So this would be the Tibetan–style opera I've heard about?

DP: Yes. So that's what I did, I stayed for a month with him and learned just one song, because they were so difficult, and it was amazing. That singing, to be able to do it, you're reaching and occupying new spaces in your body and your voice that you don't scrape with classic western singing, so it opened up all this different channels for me. Last year I went back to study with him again.

EM: You're on the other side of the world, essentially, and it sounds like you weren't there looking for music initially, but it sounds like you still gravitated towards anything of musical relevance or interest. The music scene over there, how would you say it contrasts what goes on in the UK and here in the states?

DP: There's no separation between music and spirituality there, it's totally sacred, both with Tibetan and Indian music. Indian music is in a completely different scale, and the time signatures, etc. are completely different than western music. The kicker is the spirituality of it. Over there it's just a mystical experience, it's in essence a union with a higher creative spirit. In Indian music, their concerts are usually at least like twelve hours long. You lose a total sense of time, and the point of that is complete emergence in the sound. In New York, they actually have every year a twelve hour Indian music concert, so you're going in and out of these sort of awake trance states the whole time. So that's one, and with the Lama Tibetan music, most of the songs are teachings and poems, some from past Dalai Lamas.

EM: Over here, if someone were to attend a twelve hour music concert, there would be multiple artists and most certainly drugs involved, but over there it sounds like your all natural music experience. Are there any additions drug wise over there, or is it pretty much you, your conscience, and the music?

DP: It's really just the music and you and your body and the thing that's swirling above your body. There's a really interesting traveler culture of music in India too—everywhere I went there were these awesome groups of different musicians jamming together. Most times I've gone to Dombashawa there have been these insane collections of world Gypsy musicians who meet there and are playing insane, wistful music. I think a lot of people go there to find themselves musically.

DOE PAORO

EM: When did you make the decision to get back to the states and start working on your own career?

DP: It became so clear for the first time, and it wasn't when I was doing the singing. Right after the singing, I came back and took a job my friend had offered me while I was away, and I was there for like two days and just couldn't do it. I was in some creative state that I had never been in before. I had read about it, I didn't understand really how I got there, but every moment I was inspired in this way that I hadn't experience before. I had this feeling that it was a sort of "now or never" situation. All I wanted to do was write songs. Before I left for Indie I couldn't write anything, but when I got back these songs were just falling out of me, and every moment I would be writing. When I got back to New York, on the subway I was writing lyrics, I couldn't even help myself.

EM: So do you think this was really a direct stem from doing these exercises and dispatching yourself from all the clogging materialistic bullshit that, not to sound like a hipster radical, but separating yourself from the things that really don't matter, and then your mind just—

DP: Totally. I took so much time alone to be with myself, and I think taking that gestational time to isolate is really important for any major creative work. And of course I was doing all of that yoga bodywork, and the singing—I was really just feeling things on a different level.

EM: So you came from this dark shattered situation, go over there, and then whattya know; you get drawn back to music in a much more intimate fashion than ever before. It sounds like a very "meant to be" eight months, where you go out, and then you realize that you've stepped away from your calling and you come back to it with a clear mindset.

DP: Yeah, it was very fortunate timing Ronnie because everything happened right when the movie Eat Pray Love had just come out (laughs) so I was subjected to constant harassment from my friends. (Laughing) I promise that movie had nothing to do with it though, I'm not a divorcé for one.

EM: (Laughs) I believe you I guess. But, you came back and that's when the Doe Paoro project really started taking off?

DP: Precisely. I came back and spent a few weeks writing music by myself and then I called two friends, and I didn't call any of the guys from my previous band because I just wanted to start fresh. I had an Idea of what I wanted, so I wanted to work with a bunch of people and see what clicked. I called a cellist that I knew and then I called Adam, who I actually went to camp with when we were children. I heard that he had just moved from New York, and I'd heard he was a really good pianist so I asked him if he wanted to try writing some music together and then we just … never stopped.

EM: The first big project that came from that was the album Slow to Love. The album, when I listen to it, I get this general sense of introspective, drifting—in and out connectivity, if you will—where it's almost haunting in a way. It's one of the weirder albums I've ever listened to, from a relation perspective—it's an interesting thing to relate with. It seems that a lot of the album, when you know what you had just gone through, really pulls from those experiences.

DP: I can say this because I've made music in the past that's based on some fictionalized idea I had for myself, or maybe some extension of what had happened in real life, but this was the most honest thing I'd ever made. And I knew this—what was happening—which was so strange for me after skirting the issue for so long when I was creating things.

EM: Right, and it's your debut album as Doe Paoro, and it offers a sort of transparent glimpse into your mind and what was going on with you and that's a beautiful thing to have with an album, especially one that you're introducing your name to the world with. The current members, Yuri, Adam, David and Sean—were they involved in that project?

DP: No, just Adam and Yuri.

EM: Adam's involvement in that album in relation to your newer stuff, for example he's been working with you closely on that project with Justin Vernon. It seems like—not to take away from the current members—but the two of you seem to have a better connection than everyone else. Is that because the two of you just simply have a similar creative mindset about things?

DP: Yeah, Adam and I have a really keen connection. We can tap into the same moment and have similar feelings about music in that sense, and from the start working with him as never something we had to—we never talked about music we just made it. The process came so naturally and was so joyful.

EM: That sort of easy going connection in terms of composing music with someone is rare, and a gift that shouldn't be put to the wayside. That sort of fluid connection feels so rare—I've made music with friends before, and my best friend who I've known since I was four years old—we couldn't make music together if you put a gun to our heads, we just can't do it. When you find that connection with someone making music you have to hold onto it, becuase you don't know how often that will come about.

DP: It's really such a gift, being able to speak the same language with someone musically like that, and you're right. It is rare. Just because you're good friends with someone doesn't mean you'll speak the same musical language.

I've made music in the past that's based on some fictionalized idea I had for myself, or maybe some extension of what had happened in real life, but this was the most honest thing I'd ever made.

EM: It's been a year since [Slow to Love]. So comparatively to your current projects, how does that album differentiate from the Doe Paoro of today?

DP: I think the stuff we're working on more now is sonically going to have a lot tighter production on it. I tried out a lot of things on that album, and it was important for me to self release it and not go with a label because I wanted total control, I wanted that freedom to see what worked and what didn't and to put it out in that free state. Our newer stuff is definitely more focused on the RnB, the Dub kind of layered textures and move away from the more folky elements. No rap, but we're pulling from inspiration in Hip Hop music with the drums and phrasings, but conceptually it's a continuation from what Slow to Love was. It was one idea of love, and moving forward I want to explore how you get those ideas of love, and where they come from. I've been thinking a lot about the cyclical nature of habits and where they come from.

EM: So what you're trying to do is try and keep Slow to Love relevant but progress with where your music is going?

DP: Yeah, because the album (the first one) is honest, it can't be abandoned. I can't totally abandon everything I was a year ago.

EM: Well of course, and I think that makes a lot more sense with you compared to other bands because the whole Doe Paoro project came out of everything that album was built off of, and it wouldn't make a whole lot of sense just to leave it in the dust. From that album, "Born Whole" is an incredible song. It drew me into Doe Paoro. The video for it—your average passerby is going to hear a cool tune and then see this obscure video that isn't exactly the easiest to put together. What are the connections between the video and the song?

DP: There are so many amazing parallels, I love that video for a bunch of reasons, but conceptually "Born Whole" is a loop. We made the whole song on a loop of two chords that are in the entire song, and it's about the loop of a life cycle in many ways. The video is essentially exhibiting that loop. My best childhood friend, Miranda Siegel, directed in Syracuse maybe a few miles from the house I grew up in. It's basically this idea that what makes you half of a person is your inability to learn from any situation, where you continue to go through life with blindfolds on. You get caught in this hellish cyclical existence.

EM: You worked with Miranda on that, who also filmed "Body Games", which is a completely different experience. How was it filming in Finland?

DP: The video for "Body Games" was a much bigger production because we were filming it in Finland. There were a lot more people involved, a lot more props—including this eighteen foot wig we brought all the way from New York to Finland.

EM: It seems like every song in the album is intertwined—is there any sort of continuance between the two videos as well?

DP: Miranda is such a perfect collaborator for me, visually, because our ideas are based in the same root values. She's also a Vipassana meditator, so we operate on the same wavelength, and are both interested in cyclical nature of existence and your own power to break bad habits. So the tie between the two is breaking cycles. You've got these two girls who are in some sort of relationship that is very strong, and it's clearly that they've become too close when their hair joins heads. The idea of it is that you can control that, you can be your own person, and cut your hair and start over.

EM: Right, and it seems like a very clear examination on escaping that sort of "hamster in a cage" lifestyle. You've been able to surround yourself—especially since you started on the Doe Paoro project—with people that you know, that you've worked with before and have had a connection with. People that luckily are able to help in a way that isn't just going to be a one-time thing. That’s a smart business move, but it's also a really nice thing to be able to have.

DP: It is, it's such a blessing and I feel really fortunate for that, to have such talented friends and, like you said, to be able to create with them.

THE FUTURE & SXSW

EM: You’re currently writing your next album and working with Lasse Martin (Lykke LI, Niki & The Dove). Nobody knows much at all about that project. Just in general, you talked about how it's going to be sort of a quasi-continuation with more of the electronic element—a little more complex. But from working with him—did he produce the entire album? Or is he producing?

DP: Remains to be seen. We'll figure out the production once we get a label on board most likely, cause I'm probably going to release this one with a label. So not sure who's going to produce it yet.

EM: Was he more involved than just the sound mixing and things of that nature?

DP: At this stage he's been involved in setting me up with a lot of different Swedes to write with. We have been working on a few demos together, I'm producing some.

EM: Do these two singles that you have coming out with White Iris in June, were they anything you worked on with him?

DP: No, those were two songs I wrote without him. Actually, they were produced by Ben Rivers.

EM: Right, Fever Ray. And so those two songs, are they going to be on the upcoming album or are they just a separate project?

DP: I think they're a separate thing.

It's such a blessing and I feel really fortunate for that, to have such talented friends and, like you said, to be able to create with them.

[soundcloud url="https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/42921928" params="" width=" 100%" height="166" iframe="true" /]

EM: Is there anything out yet at all or is everything with that upcoming album in the fetal stage, if you will?

DP: It's in the fetal stage. Certain songs are in various stages of development. We have one song that's fully produced but really I've just been out here … I wrote an insane amount this month. I think I wrote like twenty songs or something.

EM: The old "whip out as many songs and choose your ten best."

DP: I mean, yeah…it's just been crazy because I don't even know what I've made.

EM: That is a process that no one knows about unless they work in the music industry. It's almost as if for 90% of albums that are out there, if you're working with a record label you usually put together way more songs than are going to be on the album. From everyone I've talked to, if you get bunched up, it creates a pretty hectic scenario. So you've got the templates down for all of these, but do you feel like you're going to be able to look at these twenty or so songs and once you figure out the ones you really like, refine them and turn them into something that is more than just, "hey, I had to whip this together"?

DP: Oh yeah. The thing is, we have some other songs aside from what I've written here. I've been writing some really epic pieces with Adam, including that song that Justin Vernon is producing at the moment.

EM: Speaking of that one … it was written about Hurricane Sandy? Or just inspired by it?

DP: We wrote it after. Adam sent me this idea. He wrote it during the hurricane and he was like, "this is crazy, you need to hear it." He kind of wrote it in what he would say was a trance state or something—he was so into it. I listened to it and wrote the lyrics in a similar state of mind … They just kind of came to me. It was in this strange time when the trains were shut down. You couldn't really do anything. Everybody was just kind of walking around wondering about how nature can just shut down your life at any given point.

EM: You guys did that song and you've got Bon Iver producing it. It doesn't sound like you sat down with him and he said, "here's what I'm going to do with this song." Rather, you've been vicariously through email working with him. How has that experience been?

DP: It's been really cool. It's amazing that he's gotten involved. It was because I was listening—like I said, we were looking for a producer. I played it for two people and they both said the same thing. They said, "this feels like something Bon Iver would be." I was like, well, let me just see, it's not like I have any contacts or anything, but I found an address and wrote to him. His brother manages him and basically said “wow, this is really great, we definitely want to get involved.” So we've just been sending him the tracks. We gave him free reign. Before he started, I'm sure he's heard some of what we do but also we just wanted him to do his thing. We got a rough mix last week and it sounds incredible.

EM: That's cool. And so that is for you … no offense, but you're not a huge artist right now, so getting someone like that to step in must have been sort of a "holy shit" moment when you realized that was going to happen?

DP: Yeah, totally. I didn't even know it would happen. He said he was really into it and they were telling me it was happening. But 99% of things that are promised to you in the music industry don't come through, so it's this constant game of surrendering your expectations and getting ready for disappointment. I was ecstatic when we first heard that he even liked the song. Like, okay, that's great, that's enough. And then we heard that he was going to produce it … I don't think I even believed it until we got the rough demo and then I finally kind of wrapped my head around it.

EM: It's just, that is an opportunity that as a small Indie artist, there's not a lot of comparisons. You've got one of the kings of—it's not even really Indie but it is, if you want to throw it under one of the categories—kings of the experimental Indie chillwave whatever movement. Anyone who likes that type of music knows who Bon Iver is and here you are getting one of your tracks produced that isn't just another track, too. It's a track that sounds like it means something and it has some sort of societal relevance. It's not going to be just another song. It'll be a message. Are you guys thinking about getting anything involved for when it's done to help contribute to Hurricane Sandy or something like that? Or is it just one that he wrote during it?

DP: It was just a thing we wrote during it.

EM: SXSW is in arms reach. You're playing four days in a row down there. You’ve got your White Iris records party. Obviously you work with them, they're your label, so that makes a lot of sense. You’ve got your showcase at the SoHo Lounge, which I went to last year—that's a pretty sweet spot. I don't know much about the House of Nokia. It'd be really funny if they had those really old joke phones that people laugh about now lined all over the walls. And then you've got your Wild Honey Pie party. This isn't your first SXSW, correct?

DP: Right. You've been there, correct?

EM: Yeah. It's so exhausting. There's so much shit going on all the time.

DP: You've been there, right?

EM: Yeah. I went down there last year on business and it was cool, but it ruins the experience when on business because you're so stressed the whole time. You've got like twenty meetings in six days and you're just like, oh my God.

DP: Yeah, it's so intense.

EM: SXSW is arguably the most important festival each year in the music industry, just from an all-around standpoint. Even really with movies too, but they've got a lot of other ones like it. You have this two and a half, three week long showcase of everything you want to know about that's new in music. You were there last year. You're going back this year. What are you doing differently to get prepared that you didn't do last year that you wish you had?

DP: I think the biggest thing for us is we have had so much experience playing live this year compared to last year. When we played last year, we were totally a new set. I think we had played only four shows together. Now we've added a bass player. Last year it was just the four of us. We're playing new music too. So I think just what we could offer with our live show is so much more intense. When you're not thinking about what you're doing up there, when it becomes more habitual as opposed to those first early shows where the technical stuff is the focus, that's when you have the potential for this truly transcendent experience between the people performing and the people listening. I think sometimes we really get there.

EM: It sounds like for anyone who does performance with their career, once you get past that first hump where you are up there and you can't stop thinking about stupid shit like, "what do I do with my hands right now?" you can move into the spot where you want to be where it really is just you, the music, and the crowd.

DP: Yeah.

EM: From a preparational standpoint, you did it last year, you're doing it this year. Do you have any tips that you would like to throw out there in case any newbies that are playing this year are reading the article?

DP: Oh, gosh. Drink lots of water. Rest before your show. The whole thing's exhausting. You're out in the sun, you're having so much fun and seeing lots of music. The important thing is if you're there to play, make sure that you're doing that right.

EM: Right. All of the recommended hullaballoo about being an artist and not drinking the night before and ruining your vocal chords and whatnot—that’s something that with a relentless event like SXSW, you actually need to pay attention to.

So you've got those four shows there. Just a brief look into the future of Doe Paoro. Maybe sometime later this year your sophomore album will release. We've got the two singles we talked about coming out in a little while, this video with Dreambear that we’re premiering today, then the Bon Iver project, if you will. What else do you guys have going on with 2013?

DP: 2013. Those are the big things. The key for us in this next year is going to be getting the whole album together and putting that out, and seeing what opens up for us after SXSW. We're still trying to figure out the booking agent piece of things. Hopefully touring a little bit off the White Iris release too.

Doe Paoro is a fascinating new artist who's more about the message than the music—an admirable quality that seems to grow rarer as the days go bye. She is an active practicer of Yoga and Vipassana meditation. She is currently signed under White Iris Records and resides in New York where she is working on a sophomore album. Her debut album Slow to Love is available for purchase through the various music capitals, links are provided below. For more information on her, visit her website and follow her social networks, or keep track of her right here on Earmilk.com. She's actively pursuing all options for a booking agent right now.