In interviews, Kendrick Lamar says good kid m.A.A.d city is a far cry from Section.80. Where Section.80 passed comment on Lamar's generation, good kid m.A.A.d city provides background for that appraisal. Not only do we gain a better understanding of Lamar through his personal histories, we also gain insight into the personalities of his peers ScHoolboy Q, Ab-Soul and Jay Rock. Good kid m.A.A.d city is a definitive album for Compton – though it is not without its flaws.

The story told over the course of 12 songs – plus however many bonus tracks – is one of self-awakening, as much for the listener as for Lamar. The storyline is roughly as follows: Lamar "borrows" his mother's caravan. He takes it to see his girlfriend Sherane – whose brothers ambush him? Lamar speeds off into the night to wreak havoc with "the homies." He trips off a laced blunt. Drinks it off while his homies jump back in the van to shoot up Sherane's brother. All of which takes place in a 24-48 hour span – probably.

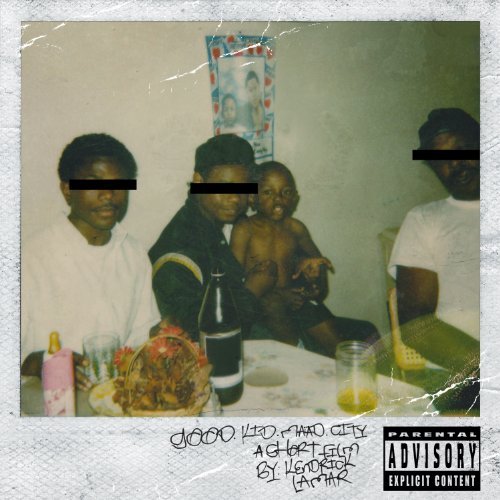

The story, what Lamar dubs "a short film," is highly intricate and is oftentimes overshadowed by typewriter-punch flows and crisp beats.

"The Art of Peer Pressure" begins a laid-back medley of piano, whining synths and upbeat drums – a sort of resigned sing-along to the "high" lifestyle. But then drops into a distorted lament – beat by Tabu – about a blunted ride-along gone awry. Let's just say Lamar was lucky not to have had the caravan impounded.

"Money Trees" comes next and is a frighteningly bumpin' riding song; frighteningly in that the beat slaps hard, is cradled by sunshine-laden synths – perfect for the car – but at the same time is drenched in irony. Lines such as this one really take the fun out of maxing your stereo: "Dream of living life like rappers do, bump that new E-40 after school, you know big ballin with my homies, Earl Stevens had us thinking rational."

But Lamar's not done: "Back to reality, we poor, ya bitch," he raps – begging some interesting questions. Such as: Is it helpful or harmful to treat hip-hop as an escape? What about the countless Lamar's who don't flip their imagination into reality?

"Good kid," the record produced by Pharrell, is another standout. Lamar seems to strap himself inside a straightjacket and use his lyricism to break free. It takes him three verses, with two crescendoing hooks that are really just more rapid-fire cries for peace of mind.

The arrival of "m.A.A.d. city" nulls those pleas – as soon as you hear ScHoolboy Q's wild battle cries echo down Rosecrans.

The only less-than-flattering part of good kid m.A.A.d city comes via the bonus tracks. The structure of the album implies the bonus tracks are an indication of Lamar's musical direction – now that he's "made it."

"Now or Never", featuring Mary J. Blige, is a poppy saccharine number that includes the lyrics, "I'm so high I can touch the sky." It's produced by pop producer Jack Splash.

It's not so much the record is poor – it's just happy. Aren't "artists" supposed to be tortured and torn? Presumably yes, and surely Lamar will be in the future. But for now, he's doing right by his mama, and, most amazingly, creating hip-hop with some sort of tangible context beyond hash tags and molly references. Though there is a "fuck the world" metaphor in there.